Have you ever experienced something felt so deep within your bones you consider it to be life-changing?

On Thursday night I attended a performance of Hamlet at Aviva Studios in Manchester, which featured orchestration by Radiohead's Thom Yorke using music from the band’s 2003 album Hail to the Thief. Honestly? I feel changed by it. Such was the intensity and physicality of the performance as a whole that I can’t stop thinking about it. Samuel Blenkin, playing the titular role, was gripping. The way music and dance was weaved throughout meant I couldn’t look away for the whole 90 minutes. It was dark and visceral and unrelenting and sad and funny.

Of course, I had to go for a pint and sit down afterwards, to help myself come down. But as I did so I realised in witnessing such a brilliant act of creativity my very soul itself felt nourished. I was full to the brim.

There are moments in life, sometimes major, sometimes fleeting, but they leave a permanent mark on you. My first sip of IPA at Odell Brewery, devilled kidneys on toast at St. John, Mills Foxbic at Hereford Beer House, the reuben on rye at Choice City Deli. These are experiences that helped shape my worldview. Now I will never be able to consider Hamlet as a play and HTTT as an album in the same way ever again.

Something similar happened to me last summer while on a guided tour of Timothy Taylor’s Knowle Spring Brewery in Keighley, West Yorkshire. Led by outgoing CEO Tim Dewey and accompanied by drinks writer Rachel Hendry, there I had an experience that altered the way I perceive the flavour of its beers forever.

I was on photographer duty, so while Rachel diligently asked questions and took notes for her eventual article on the brewery’s signature beer, Landlord, I was focused on lines, light and angles. I shot the steaming mash tun, barrels of Goldings being administered to a fresh batch of the beer itself, and lines of lab samples; golden beer in test tubes, catching the midday sun through a brewery window. I hadn’t really clocked that we were heading into one of the fermentation rooms, but I immediately knew where we were when we arrived.

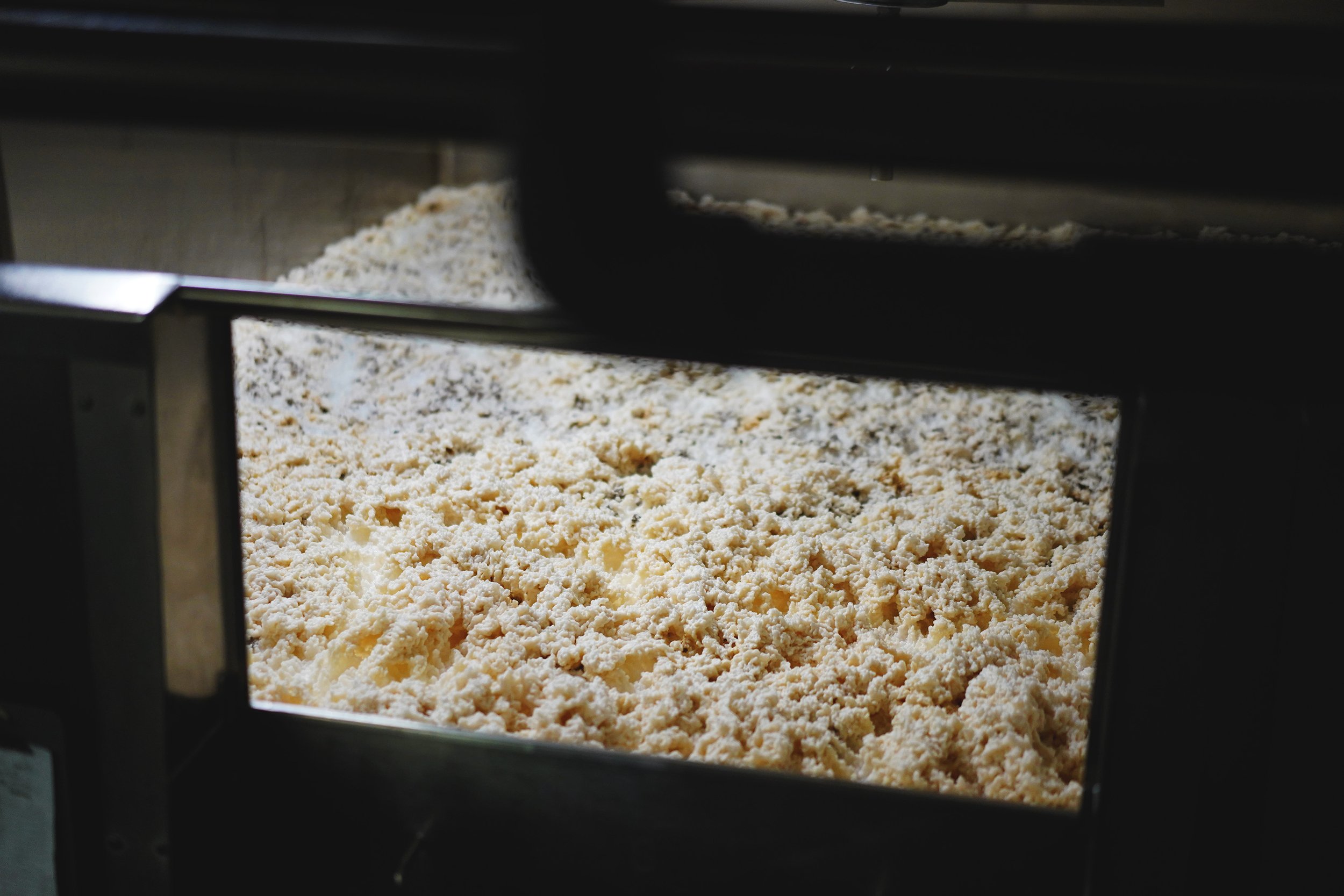

For some reason I had decided that Timothy Taylor’s fermented all of its beers, like most breweries, in tall, cylindroconical fermentation vessels. I was wrong. All of its fermentation occurs in completely open, square, stainless steel containers (although, as Tim was quick to point out, they’re technically not Yorkshire squares.)

Without warning, every molecule hovering in the air around us was saturated with the powerful aroma of Taylor’s Taste, the house yeast culture it has kept alive for decades. It was familiar, a scent I had experienced a thousand times over each time I had held a pint of Taylor’s beer beneath my nose. Here, though, it was far more intense. Like it was in my very pores and crawling beneath my fingernails. Like proving bread, stewed apricots, the must of a dry, well cared for cellar.

In the vats, the still fermenting beer was topped with a high krausen, tan-hued foam flecked with darker brown patches where that particular group of yeast had decided its job was done. It was moving. I watched as the foam gently, joyfully rolled atop each of the vats, a lungful of carbon dioxide making me feel dreamy and intoxicated.

Taylor’s Taste and I were reacquainted an hour or so later; in a pint of Landlord at The Inn on the Green, and again in a glass of Boltmaker at the Boltmaker’s Arms. I had always considered Taylor’s beers for their malt, their snap, and their minerality. But no longer. Now it was this effusive, happy yeast that didn’t just meet my senses, but enveloped them. No pint of Timothy Taylor’s beer has ever tasted the same again.